THE WORCESTER TELEGRAM & GAZETTE

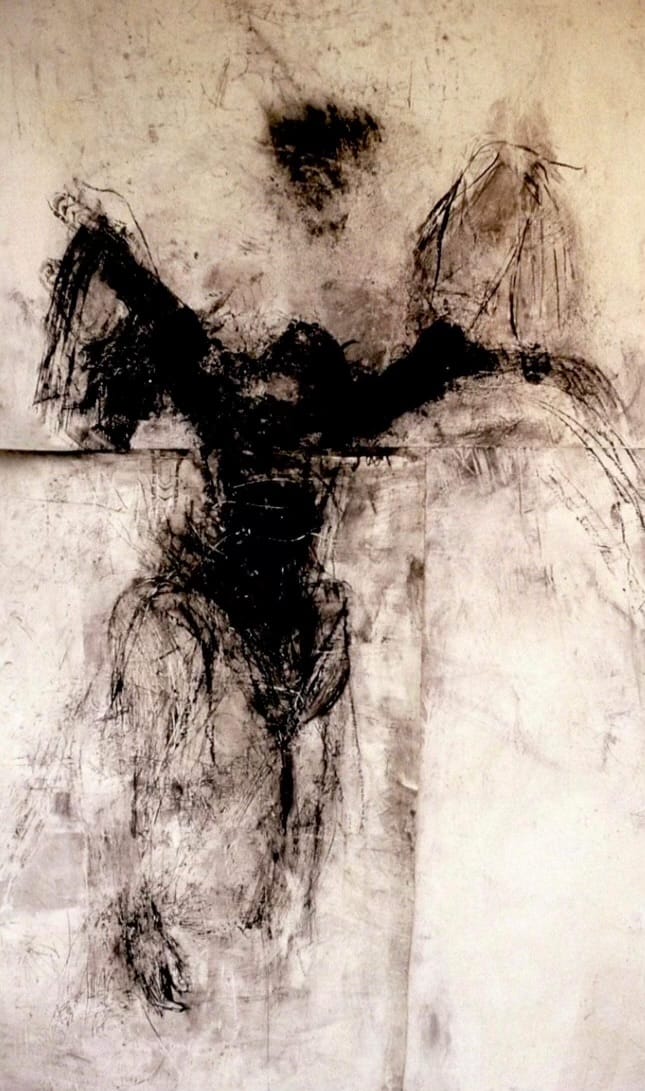

It is probably fair to say that Marilyn Solomon Kalish’s favorite drawing at the moment is “Breathe,”

Kalish’s Drawing Now Its Own Reward

By Frank Magiera

The huge, majestic, invigorating smudge of charcoal that is the centerpiece of her latest exhibition at WPI’s George C. Gordon Library. The image is just the suggestion of a figure; arms outstretched; head thrown back; one leg about to take a giant step forward, perhaps, as the torso inhales expansively.

For Ms. Kalish the piece is not just defining but transforming. She views it as something of an artistic gateway through which she has finally passed after a lifetime of treating drawings as preliminary exercises in preparation for more substantial works of art.

“I’ve always sketched. I’ve always drawn since I was young,” Ms. Kalish said. “I didn’t place a lot of value on my drawings because, historically, they were the prelude to a more important piece.” Her outlook changed when she discovered wax and figured out how to use it in her drawings.

“I’m excited about this piece because I found a place to push,” she said. “That means a lot to me.”

Ms. Kalish, who has lived in Worcester for four years, has quickly caught the attention of the local art community. She volunteers in the conservation department of the Worcester Art Museum. She is active in ARTSWorcester. And lately it seems her artwork has been starring in one exhibition after another.

She recently concluded a solo exhibition of collages at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center and one of her drawings won the Freelander Award for the best piece in Worcester’s annual Art for AIDS’ Sake show just as her exhibition of new drawings was opening at WPI.

“I’m old-fashioned in the way I approach painting,” Ms. Kalish said. “I’m not interested in intellectual concepts. I’m a contemporary artist. There’s no denying that I’m fully aware of the times we live in. Yet I pay attention to what happened before me.”

If Ms. Kalish is not interested in concepts, she is absolutely inspired by materials. When she’s not making art in her studio, she is likely to be reading about the old masters such as Titian and Rembrandt.

“I’m impressed with their integrity, the time and care that they took in preparing their materials,” she said.

Ms. Kalish’s respect for classic materials made her a perfect match for a role as a volunteer in the museum’s conservation department, where great paintings are cleaned, repaired and preserved. About two years ago she began working with museum’s Fayum portraits, the encaustic masks used to cover the face of mummies.

“They’re beautiful, seductive and gorgeous,” she said. “These were wax, not oil, and they held up better than oil. So I became very interested in that method.” As Ms. Kalish explored the techniques of encaustic, she also returned to her drawings.

“I always loved to draw,” she said. “It gave me a lot of joy. I’m a morning person. I’m up at 5 sketching and sketching. My technique is that as soon as I make a mark I’m pretty much committed to the mark.”

“So I have many, many drawings that don’t work or that are not realized for me. And then one will become realized. I spent a lot of time thinking about how to stay in the drawing longer. And then at some point my work, my volunteering and the wax converged.”

Ms. Kalish simply borrowed some of the classic painting techniques to give more substance to her drawings. For instance, she sizes her drawing paper with rabbit skin glue, much the way artists used the glue to size raw canvas to prevent oil paint from penetrating the linen or cotton fibers. Then she heats clear wax and brushes it over the surface of the paper with Chinese brushes.

The wax dries almost immediately, providing a malleable ground for her drawing. With the wax coating, Ms. Kalish discovered that she could wipe out the lines of the drawing if she decided they were wrong, without abandoning the image entirely. In fact, she discovered that the shadowy residue of obliterated lines left something of a record of the drawing process, which enhanced the final image.

“I started to draw on that with charcoal,” she said. “And if I didn’t like what was happening I could push it back with turpentine. I just brushed turpentine into the wax and the charcoal image would just push back and leave a faint, ghost-like image. It allowed me to stay in it for so long.”

The wax also allowed Ms. Kalish to use tools usually associated with painting, such as palette knives, to make her drawings. The technique also allowed her to dramatically enlarge her drawings from notebook-size to painting size. The image of “Breathe” for instance, measures 88 by 56 inches. It is made on three large sections of paper, glued and waxed together, and mounted on a rigid fiberboard backing.

“My drawings can stay large now,” she said. “That was for me—I don’t want to say a breakthrough because I think breakthrough is nothing more than working very hard and persevering. I tend to agree with Einstein’s statement that creativity is 10 percent inspiration and 90 percent perspiration. I just kept doing.”

Ms. Kalish also likes the simpler and more subtle imagery that has emerged in her new drawings.

“As I became older life became simpler,” she said. “I began to shed things. Less is more. I’m not having to explain so much. There’s a lot going on in them but they’re just not … boom! I don’t need to do that anymore. I don’t feel it’s necessary to bash you over the head.”

“Born in Springfield, Ms. Kalish grew up surrounded by art. Her grandfather was a portrait painter and she spent many hours in his studio. But as an art major at the University of Hartford in the 1960s she fell under the influence of the more fashionable abstract expressionism.

“I thought he was old-fashioned,” she said of her grandfather. Then a college instructor discouraged one of her projects, saying that everything there was to accomplish in art had already been done.

“Those were fighting words,” she said. “That was a challenge.”

Ms. Kalish said the best word that she can think of to describe her working methods is “assault.” That term seems particularly appropriate at those times when her drawing becomes so intense that she actually cuts holes in the paper surface. That is also when her experience in the museum’s conservation department comes in handy.

“I trust the pen,” she said, “I trust the assault. I trust everything that is happening. I’m excited. I work from experience rather than a concept. I don’t want to be illustrative. I want to express something more than that.”

“It’s a fine line I’m walking. There’s the image. I go and kick the hell out of it. If that holds up afterwards, then those drawings are the ones that have the most to offer.”